The Ascension Relief , marbel panel by Donatello, 1428-30. V & A Museum, London

The Ascension has been a theme in art since the 4th century when a feast was introduced in the Church forty days after Easter, in accordance with the chronology in St Luke’s account in Acts (1:6-10). The readings for the feast always include this reading but with different Gospels for each year in the cycle. In C, the Gospel is St Luke’s account ( 24:46-53). These texts from St Luke, especially Acts, provide the source for the iconography.

Ernest Dewald gives an overview of the iconography up until the end of the Middles ages in “The Iconography of the Ascension” in the American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 19, No. 3 July 1919, p277-319, looking at examples in manuscripts, ivories, bronze, wood and stone. He traces a Hellenistic tradition in the West on the one hand, where Christ is shown ascending in profile from a mountain with the apostles below, which can be seen in a panel of the Santa Sabina doors and in an ivory diptych in Munich from the late 4th century, and on the other hand, he identifies a Syro-Palestinian tradition, where Christ is in the heavens in a mandorla and the Apostles in a separate zone below as in the Rabula Gospels now in Florence from 586. By the early Middles Ages, the Syro-Palestinian model, which dominated in Byzantine art, had greatly influenced the West and become the main type. We can see this in the bronze doors of St Paul’s Rome, though the Hellenistic influence continues to be seen in the figure of the ascending Christ in profile in many examples as in the Drogo sacramentary and there are other variations and combinations in between.

An entirely new one then developed in late Anglo-Saxon art in the early 11th century in the Missal of Robert of Jumiege from Canterbury, seen in the 12thc Sacramentary of St Bertin and spreading via Paris throughout the West. It was coined by Meyer Shapiro as the ‘Disappearing Christ’ in a seminal article.1 This type dominated the period 13th– 15th centuries, though other traditions continued. Here, only Christ’s feet are shown and the focus is on the apostles in the lower part. Shapiro sees this as a late visual response to Patristic exegetical tradition of the Ascension. However, it is interesting to note that Giotto, both in the Basilica at Assisi and in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua returns to the original Hellenistic prototype, while near contemporaries such as Pacino da Bonaguida used the conservative Byzantine model.

Donatello’s Ascension relief in the Victoria and Albert Museum London, executed 1420s, comes from a hundred years after Giotto, and a similar period of pictorial innovation. He draws on all the different iconographic traditions, for the 11 apostles and the Virgin Mary, for the mountain scene and the presence of angels, though the added theme of Christ giving the keys to St Peter has clearly affected the composition. It is considered very likely that it may have been part of the original scheme for the decoration of the Brancacci chapel alongside Masaccio’s frescos of the life of St Peter in the Carmelite church in Florence for several reasons ( though provenance only extends back to the 1490s): the date of the relief matches the commission; the correspondence in style and in the innovations in perspective, composition, use of cast shadows, and treatment of the figures when compared with Masaccio’s frescoes, in particular the Tribute Money, where layout of the apostles is the same all seems to indicate a link; nowhere else does Donatello use this compositional arrangement; the relief includes the handing of the keys to St Peter, an essential episode in the life of Peter, but omitted from Masaccio’s cycle in the Chapel, suggesting it had been reserved for Donatello’s relief, possibly intended for the tabernacle or altar front; the iconographic detail of Jesus ascending from a mountain and handing the keys to St Peter would fit with the Carmelite tradition that it was St Peter who had brought the good news of Christ to the hermits on Mt Carmel, to whom the Carmelites traced back their origins and it also matches an eye-witness account by the Bishop of Souzdal of a mystery play including the Ascension scene as performed at the Carmel in 1439 in which the handing of the keys and the Ascension are linked in the same way as in the relief:

…at this point a clap of thunder resounded through the church, and a cradle, masked by painted clouds, descended from an aperture above the stage. During its ascent, an actor,representing Christ took up two golden keys, and blessing St Peter handed them to him…. 2

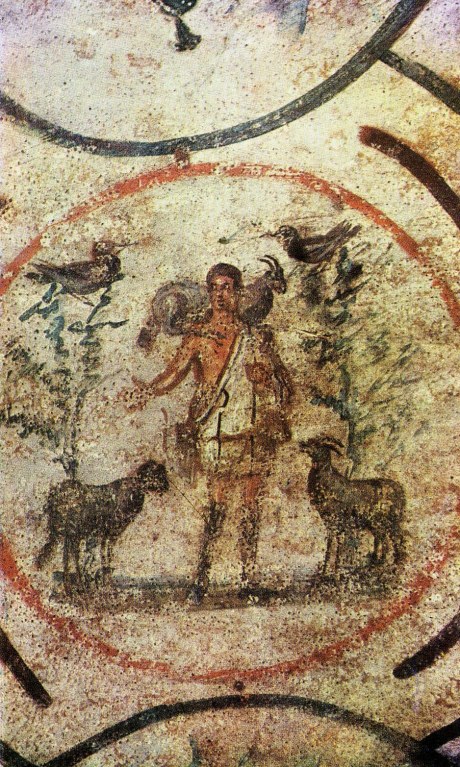

Vasari praised Donatello for his invention of low relief known as rilevo schiacciato (flattened relief)) and this is one of his finest works using this method. It is as if Donatello is drawing in light and shade. Using low relief and Brunelleschi’s innovation of linear perspective, he was able to recess a large number of overlapping figures, create an illusion of depth and precisely locate the spectator in relation to the scene. Even though the relief is a fraction of the depth of Ghiberti’s earlier Agony in the Garden, Donatello could overlay five figures of apostles and Mary on the left and six figures on the right, where Ghiberti was constrained to two. The viewpoint of the spectator is below the line of the apostles feet, as we see the more distant apostles and trees as lower than the nearer ones. This helps also emphasise the vertical movement of the ascending Christ, in the horizontal composition, and like the other trees on the left, draws the viewer’s eye to the distant background scene.

The figures are remarkably solid, and there is drama in their expressions and faces. The Virgin Mary is seen from behind, has the solidity of the Virgin Mary of Masaccio’s Pisa Altarpiece in London’s National Gallery. Angels on the left console each other in grief, or astonishment and wonder.They too, are affected by this moment of departure. The clouds partly obscure Christ and help to situate his figure in space, as do the angels who surround him. Christ is not standing but as if seated on clouds, ascending while in an attitude of authority.

Donatello boldly takes on the difficulty of representing a supernatural scene without flinching from the bodily nature of the mystery. In fusing the event with the handing of the keys to St Peter, probably in accordance with the commission for the Carmel, he links the Ascension, and Christ’s exaltation more concretely to the mission of the apostles and church in bearing witness to him, and links their authority to his divine power.

By representing Christ frontally and with attention to the solidity of his body, only veiled partly by clouds, Donatello finds a way to present Christ’s ongoing presence in the Church.

1. Meyer Shapiro ‘ The Image of the Disappearing Christ: The Ascension in English art around 1000’ Gazette des Beaux Arts Sec 6. Vol XXIII, 1943

2. See quote in B. Bennet and D. Wilkins: Donatello Oxford, 1984 p139